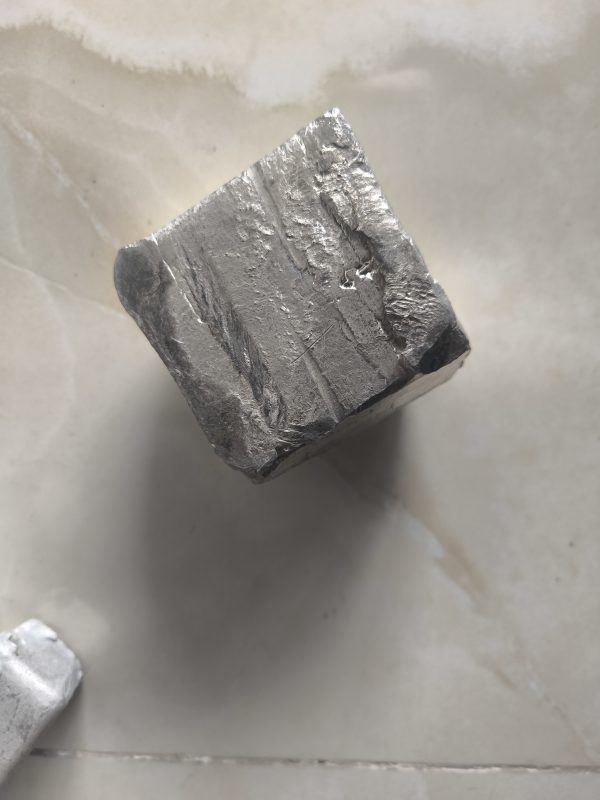

Indium (chemical symbol: In, atomic number: 49) is a rare, soft, silvery-white post-transition metal. It exhibits unique physical and chemical properties, making it crucial in electronics, optoelectronics, and advanced manufacturing. Here’s a detailed overview:

- Physical Traits: Incredibly soft (softer than lead) and malleable, with a low melting point (156.6°C) and a boiling point of 2,072°C. Its density is 7.31 g/cm³. A notable characteristic is its ability to “cry”—when bent, it emits a high-pitched sound due to the fracture of its crystal structure.

- Chemical Behavior: Relatively stable in air at room temperature, forming a thin oxide layer (In₂O₃) that prevents further corrosion. It reacts slowly with dilute acids but is resistant to alkalis. It can alloy easily with metals like gold, silver, and tin.

Discovered in 1863 by German chemists Ferdinand Reich and Hieronymus Theodor Richter while analyzing zinc ore. They identified it through a distinctive indigo-blue spectral line, hence the name “indium,” derived from the Latin word indicum (meaning “indigo”).

- Natural Abundance: Extremely rare in Earth’s crust, with an average concentration of ~0.049 parts per million (ppm)—about three times rarer than silver. It rarely forms its own ores; instead, it is a byproduct of zinc mining (since it often substitutes zinc in zinc sulfide minerals like sphalerite).

- Extraction: Recovered from zinc smelting residues via processes like solvent extraction or electrolysis, which separate indium from other metals (e.g., lead, copper) in the ore.

- Electronics & Displays: The most critical use is in indium tin oxide (ITO)—a transparent, conductive film. ITO coats LCD screens, touchscreens (smartphones, tablets), flat-panel displays, and solar panels, enabling both electrical conductivity and light transmission.

- Low-Melting Alloys: Indium is alloyed with gallium, tin, or bismuth to create low-melting-point alloys (e.g., melting at <100°C) used in fire sprinklers, solders for delicate electronics, and thermal interface materials (to conduct heat between components like computer chips and heat sinks).

- Semiconductors: Used in semiconductors for infrared detectors, lasers, and light-emitting diodes (LEDs), particularly in high-frequency devices.

- Nuclear Technology: Its isotopes (e.g., indium-115) are used in neutron detectors due to their high neutron-capture cross-section.

- Aerospace & Medicine: In alloys for high-performance bearings and as a coating in medical devices (e.g., pacemakers) for its biocompatibility.

- Scarcity & Supply: Indium’s reliance on zinc mining makes its supply vulnerable to fluctuations in zinc production. Its critical role in electronics has raised concerns about resource scarcity, driving research into alternatives (e.g., graphene or silver nanowire films to replace ITO).

- Price Volatility: Due to limited supply and high demand, indium prices are highly volatile, often exceeding $1,000 per kilogram.

- Toxicity: Metallic indium is relatively non-toxic, but its compounds (e.g., indium trichloride) can be harmful if inhaled or ingested, affecting the lungs and kidneys.

In summary, indium’s unique blend of conductivity, transparency, and malleability makes it irreplaceable in modern electronics, though its scarcity poses long-term challenges for sustainable supply.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.